Early Navigation Projects on Green River, 1828-1842

(from: The Falls City Engineers: A history of the Louisville District, Corps of Engineers United States Army)

The first American pioneers to settle in the Green River Valley used the river and its tributaries to send produce in flatboats to New Orleans, but Evansville, Indiana on the Ohio just below the mouth of the Green, eventually became the marketing center for Green River commerce. During much of the nineteenth and for several decades in the twentieth century, the Green River Valley supplied Evansville saw mills and wood-working plants with timber; Evansville claimed in 1898 to be the largest hardwood manufacturing center in the world. Logs cut on the Green River or its tributaries in July were allowed to dry until winter, then pinned together with wooden pegs in rafts and floated down to Evansville.

The steamboat McLean was the first to reach Bowling Green in 1828, and it was followed by other boats each high water. In 1828 also, Kentucky established a Board of Internal Improvements, which requested the loan of United States Army Engineers for surveys of streams in Kentucky. Lieutenant William Turnvull and Lieutenant Campbell Graham, Topographical Engineers, surveyed the Green River in 1828 and turned the results over to the state Board. As part of its state-wide internal improvements program, Kentucky authorized development of a slackwater project to improve navigation up the Green and Barren rivers to Bowling Green in 1833, and employed an experienced civil engineer, General Abner Lacock, former Congressman and Senator of Pennsylvania and engineer on the Pennsylvania canal system, to locate the locks and dams. The Green-Barren River project was the first improvement of its kind in the United States, and canal engineers were the men with the most closely related experience. (As previously mentioned, construction of a slackwater project became known as a "canalization" project; this is, to make like a canal.)

William B. Foster, also a Pennsylvania canal engineer, was first resident engineer in charge of construction, but because of ill-health he resigned in early 1835 and the project was completed under the direction of Alonzo Livermore, another Pennsylvania canal engineer recommended by General Abner Lacock. Construction of Locks and Dams Nos. 1 and 2 was underway when Livermore took over; however, Livermore modified their designs to increase lock chamber dimensions to 160 feet long by 36 feet wide. He selected sites of two more locks and dams on the Green (Nos. 3 and 4) and one on the Barren (No. 1) to establish 175 miles of six-foot slackwater navigation from the mouth of the Green up to Bowling Green on the Barren. The locks were constructed, under contract, of sandstone masonry laid in Louisville hydraulic cement (except No. 2 which was laid in common lime). To overcome a gradient of 78 feet in 175 miles, the locks averaged fifteen and a half feet of lift. The dams were timbercrib, rock-filled structures with masonry abutments.

Several contactors failed on the project, and other problems were experienced -- chiefly resulting from poor foundation conditions and damages to completed work by floods. A flood in 1840, for example, breached an abutment of Lock and Dam No. 3 and carried away the lower lock-gates. Exclusive of the costs of snag-removal and general channel clearance, initial construction costs aggregated $780,000 -- about $10,000 per foot of lock-lift. This cost was about triple the original cost estimates; however, the fist estimates were for smaller locks and lesser-quality materials and did not provide for such contingencies as the costs of repairing flood damages.

Though the project was not entirely completed in 1841, the steamboat Sandusky locked through to Bowling Green late in the year, thereby clearly demonstrating, one contemporary observer said, that "the removal of the obstructions to the navigation of all the great rivers of the West is practicable." Over $2,000 in tolls were collected during the first year of operation and fears that the project would form a health hazard and would be a waste of money were dissipated. Residents of the Green Valley readily acknowledged the "advantages derived from a perpetual line of the finest water navigation in the world." Regular steamboat trade between Evansville and Bowling Green was inaugurated; citizens of Bowling Green constructed a six-story warehouse at the river and a mule-powered railroad to connect the landing with the business section; and the project provided a substantial economic boost to the commercial development of the region.

Free Navigation on the Barren and Green, 1865-1890

The navigation structures on the Green and Barren rivers were damaged and their maintenance was neglected during the Civil War, and in 1868, rather than expend the funds necessary to repair the project, the state legislature leased the works to the Green and Barren River Navigation Company, an organization of bankers, attorneys, and steamboatmen led by W.S. Vanmeter, the steamboat captain who had obstructed Lock No. 3 for the Confederacy in 1862. The company operated the project, opened mines and entered other business, and ran its own steamboats, the Evansville and the Bowling Green. Since company-owned vessels paid no tolls, the company soon drove competition from the river and established a de facto

monopoly.

Opposition to the monopoly soon developed, and it had very influential leadership in the person of General Don Carlos Buell, former Union General who settle in the Green Valley (at Airdrie, Muhlenberg County) after the war, opened coal mines, and began shipping coal down river to Memphis in late 1865. His business grew until 1868, when the navigation company took over the project and, with its toll-free privileges, undersold him and drove him from the market. General Buell lead a campaign to end the company monopoly and free the river of tolls. When his efforts failed in the state legislature, he took the case to Congress contending:

If the claim of Green River to the care of the Government as a public avenue rested on nothing but the expressive fact that at one period in our civil war the slackwater navigation served as a valuable channel of supplies for a Union army at a critical moment when all other lines failed, the question might properly be dismissed. But the ordinary trade of the Green River country has been relatively large from the earliest settlement, and the magnitude of its undeveloped resources especially in minerals, demands for it the facilities of an extended interstate commerce.

General Buell's complaint that the company rested "like an incubus on the destinies of the Green River Valley" brought Congressional action in 1879. An investigation ordered, and the Corps of Engineers reported that tolls on the Green and Barren rivers were excessive and that a monopoly did exist. Congress directed the Corps to ascertain the steps necessary for federal purchase and toll-free operation of the project, and a special Board of Engineers convened at Bowling Green in 1886. The Board conferred with directors of the company, inspected the project, reported that an injurious monopoly did exist, and recommended "in justice to the country tributary to the Green and Barren rivers, the present obstructive tax on its commerce should be removed." The Kentucky legislature ceded its rights to the project to the United States in 1886, and Congress purchased the company franchise for $135,000 in 1888.

Lock No. 3, the one most heavily damaged during the war, collapsed in 1887; other locks were in poor condition; the channel was littered with snags; and through navigation on the river had been suspended when the United States took over the project. Lieutenant William "Goliath" Sibert, Corps of Engineers, was assigned the duty of reopening the river to navigation. Sibert, a physically large man, had roomed at the Point with diminutive David Gaillard --hence Sibert's nickname "Goliath." His work on the Green and Barren river project was his first civil works experience and it launched him on a distinguished engineering career which took him around the world, but he was to call the Green River Country home ever afterwards. Sibert established an Engineer office at Bowling Green, arranged construction of the snag-boat William Preston Dixon to clear the Green River of snags, and initiated an emergency reconstruction of Lock No. 3 to reopen the river.

Difficulties were experienced in pumping water out of the cofferdam at Lock No. 3 in 1889, and in 1890 Lieutenant Sibert called in a waterways engineering expert, Benjamin F. Thomas, U.S. Assistant Engineer on the Big Sandy River, who got the cofferdam pumped out in ten days, put in the new masonry, and opened the lock to navigation on 10 November 1890. Residents of the Green Valley were "jubilant" and hundreds gathered at the river to see the first boat pass through toll-free. General Buell reopened his coal mines, the timber-rafting business increased, and, because the boats could transport commodities at about half the prevailing rail rates, railroads reduced rates to meet the competition. Commerce on the river quadrupled -- as many as sixteen steamboats soon plied the waterway regularly. The editor of the Calhoun, Kentucky, Constitution wrote in 1890:

It is very observable that since Green river has been made free to all who desire to run any kind of craft upon its waters, commercial affairs are assuming larger proportions; new farms are being opened, and various kinds of manufacturing establishments are springing up along its course.

In 1899, three steamboats and a number of small vessels were plying the Rough River to Hartford; they transported 10,883 tons of freight in that year. But 1899 was just about the peak for traffic on the Rough River. The project, except for its precedent-setting construction method, was a signal failure. No extensive traffic ever developed on the Rough River, though it is possible, because of how construction and operation costs, that during its many years of operation the public investment in the project was adequately reimbursed in the form of lower transportation costs, if reductions in rail rates are included.

When R.H. Fitzhugh, assistant to Colonel William E. Merrill, examined the Green River in 1879, he reported it would be feasible to construct eight locks and dams above Lock and Dam No. 4 (at Woodbury, Kentucky) on the Green River to extend slackwater navigation to such communities as Brownsville, Munfordsville, and Greensburg. Fitzhugh explored Mammoth Cave, reported that the water in the cave was the same level as the river, and concluded that a slackwater project would have no more effect on the famous cave than an ordinary rise in the river.

No action was taken on the Fitzhugh report, but concurrent with successful reopening of the old state project on the lower river, another examination of the Upper Green was authorized in 1890. Lieutenant William L. Sibert reported the construction of two additional locks and dams (Nos. 5 and 6) on the Green could open mineral and timber resources of such tributaries as Bear Creek and Nolin River to development and establish waterways transportation to the popular resort area at Mammoth Cave. Congress approved construction of Locks and Dams Nos. 5 and 6; William M. Hall moved Engineering equipment from Rough River and commenced construction; and in 1906 the steamboat Chaperon made the first run from Evansville to Mammoth Cave. A regular tourist and excursion traffic developed to and from the Cave region and commerce on the Green River system increased, but the public investment in Locks and Dams Nos. 5 and 6 was probably never reimbursed. Timber and asphalt resources on the Upper Green were developed to a limited extent, but general commerce was also served by the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and the turnpike between Bowling Green and Louisville.

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

Green River

There are some interesting and beautiful photographs of the

Green River and Lock No. 3, which is located near Rochester, KY (the

intersection of Ohio, Butler, and Muhlenberg Counties), on the web site owned

by KORBO Communications, 433

N. Main St., Beaver Dam, Kentucky 42320. Their

web site’s address is (click to go there):

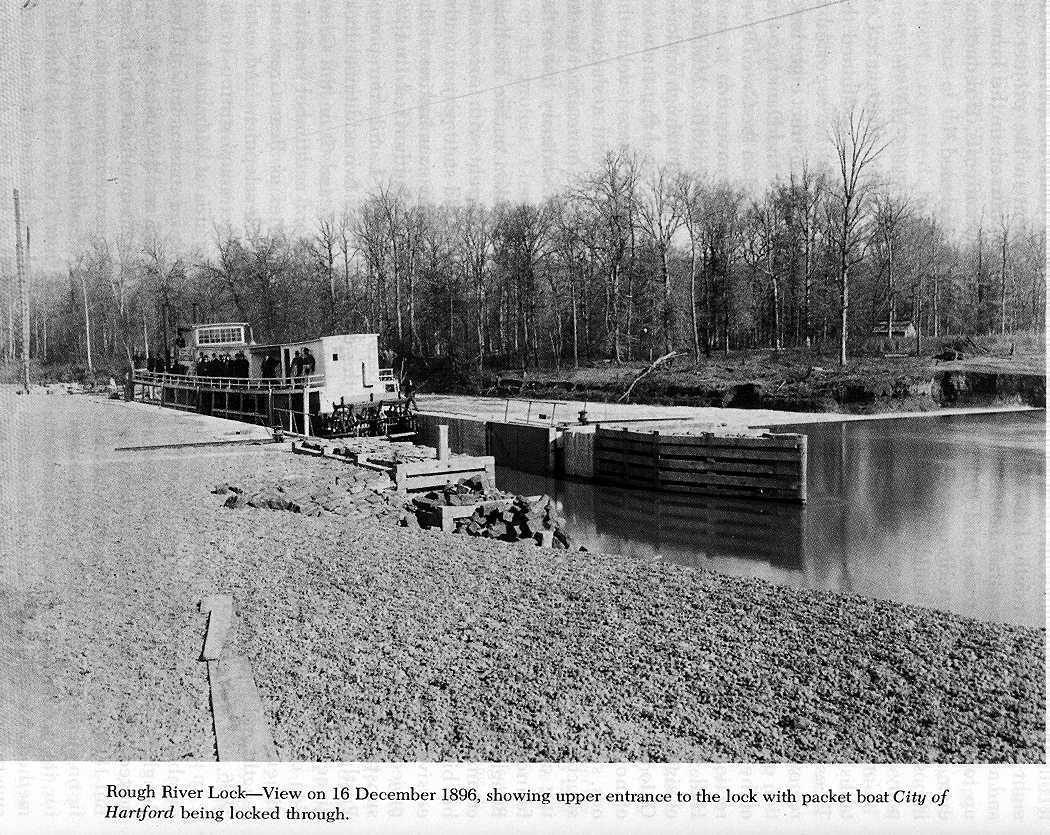

A quote from the above site is: Early steamboats were known as "packet boats" or

simply "packets"; they were owned and operated by packet companies,

which were the freight handlers near the turn of the century (from 1800s to

1900s). Keep in mind that there were few good roads in those days, and

movement for commercial and personal purposes over land was relatively

expensive and dangerous .. not to mention slow. Although the Green River

system probably has wanted for maintenance since construction was first

completed, by 1847 five steamboats were making daily trips, for example,

between Bowling Green and Evansville, and the years between 1890 and 1910 were

"the most glamorous and romantic period". In 1905 there were

nine packets on the Green River, and twenty-eight pleasure boats operated on

the river and its tributaries. It is likely that the Green River system

provided the only readily available means of transportation and pleasure during

the period. Around 1906 it was possible to leave Calhoun at five in the

evening and arrive in Evansville around daylight.

Thanks to Terry Knight for taking

these photographs and for sharing his site with us.

Visited Lock #3, Rochester, this day, 7/25/18. Rumor has it that dam will be reconstructed.

ReplyDelete